The Re-Enchantment of the Solar System:

A Proposed Search for Local ET’s

Dr. Gregory Lee Matloff

Adjunct Professor of Physics and Astronomy, NYU, CUNY, Pace University, The New School, SUNY

Co-author (with E. Mallove) of The Starflight Handbook, Wiley, NY (1989),

Fellow of The British Interplanetary Society

Member of the Interstellar Exploration Subcommittee, International Academy of Astronautics

ABSTRACT

It is argued using a conservative approach to interstellar travel that intelligent extraterrestrials (ET’s) may be present in our solar system, living in world ships that have colonized cometary or asteroidal objects during the last billion years. The originating star systems for these advanced beings could be solar-type stars that fortuitously approach our Sun within a light year or so at intervals of about a million years or nearby stars that have left the main sequence, prompting interstellar migration. If we are indeed within such a “Dyson Sphere” of artificial worldlets, we could detect their presence through astronomical means since a space habitat will emit more infrared radiation than a like-sized comet or asteroid. Interestingly, several Kuiper-Belt objects have recently been found to have an unexpected and substantial red excess. It is argued that, in opposition to the assumptions of current SETI searches, the very advanced occupants of this possible local Dyson Sphere may have as little interest in beaming radio signals in our direction as we do in communicating with termites. A research program is proposed whereby large and small college observatories would routinely monitor the spectral irradiances of Near Earth and Kuiper Belt objects while a concurrent theoretical effort models the spectral characteristics of various proposed space habitats. Much of the observational work, at least, could be dovetailed with projects designed to detect Near-Earth Objects (NEO’s) that might impact Earth in the future. Possible strategies and protocols for direct contact, requiring humans to be the active contactees are presented to be considered for use if such intelligent ET’s are discovered within our solar system.

(I) Introduction: Ancient and Modern Views Contrasted

To civilized people living in the late Bronze Age or early Iron Age, the nightly celestial spectacle was proof that humanity was not alone in the universe. The solar system was enchanted by the presence of those gods and goddesses of the ancient pantheon called Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn by citizens of the Roman world.

Although recognized today as the naked-eye planets, these objects not only had the names of the divinities they actually were the divinities to many ancients. To contact a god or goddess, a person from those civilizations might visit an appropriate temple or perhaps utilize the talents of a member of that class of soothsayers that we now call astrologers.

It is fashionable today, at least among scientists, to treat these beliefs of our predecessors as somewhat quaint and superstitious. Ever since the first Greek astronomers constructed their thought models of the solar system about 2500 years ago, science has steadily pushed back the role of divinity. We understand today that the planets known to the ancients and those more recently discovered worlds circling our Sun and others are physical places more or less like the Earth, not the abode of gods and goddesses.

To actually make scientific contact with the creator(s) of our universe may be forever impossible, due to the limits on astronomy imposed by the chaotic and unprobeable nature of the Planck Epoch, the first nano-instant after the universe’s creation.

Although science may never be able to engage in direct discourse with the Creator, scientists could constructively concentrate their efforts on contacting those godlike (although mortal) minds belonging to citizens of galactic civilizations eons in advance of our own. Even though the ultimate nature of our existence and that of the universe might elude us, such a contact would tell us a good deal about our place in the universe and the cosmic function of technological civilization.

This is the purpose of the astronomical discipline known as SETI, the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence, through the medium of radio transmissions. After several decades of effort and many SETI searches, the results have been disappointing (1). Either there are no advanced intelligences within a hundred light years or so of the Sun, or the basic assumptions of SETI are imperfect.

But recent astronomical observation and analysis has revealed that solar systems are not uncommon in the nearby universe, early assumptions about the bounds of the ecosphere , the “life zone” about stars, may have been very conservative (2), and extinct or extant life within our own solar system may be present below the surface of Mars or within the oceans of Europa (3, 4). If life is indeed prevalent in the cosmos, where are our talkative neighbors?

Perhaps they are all around us, with some migrants even within our own solar system. Perhaps we have not found them because directed-radio signals in the hydrogen and hydroxyl bands is not the best medium of interstellar communication. Perhaps very advanced extraterrestrials are not really interested in talking with us primitives.

To establish contact then, we may have to be the active party. First humanity must unambiguously detect an alien presence, then we must be the ones to clamor for attention. After all, entomologists devote little time to communication with termites. But if a termite colony signaled us in binary or Morse codes, we would immediately take notice.

Conventional SETI is dissatisfying from a human point of view. Even if we detect beamed radio signals from a cosmic civilization located a mere 30 light years from the Sun, a simple exchange of greetings would require a human lifetime. This is a long way from the promise of a Chaldean astrologer or Roman-era priest of Jupiter.

But the solar system is an immense place, both in time and space. Our exploration of this realm has barely begun. As Papagiannis has noted (5), extraterrestrial colony ships may have crossed the interstellar gulf within the distant past and may be within our solar system, in world ships that masquerade as asteroids or comets.

If we can detect these objects and communicate with their occupants, the re-enchantment of the solar system will have been established. Direct communication with these godlike elders will become possible by masers, lasers, or spacecraft. And the answers to our queries will arrive rapidly. Then, astronomers will begin to fill the roles of the ancient temple priests and priestesses. Terrestrial civilization will enter a new golden age as we learn the wisdom of the “elders” and begin to fulfil our galactic role.

Before beginning a search for a local extraterrestrial presence, we need to develop a multi-step program. First, we must consider an evolutionary model for technological civilizations, that allows for slow interstellar expansion but not necessarily signaling. Then, we must conservatively consider those modes of interstellar travel that now appear to be feasible for a technologically advanced galactic civilization. The next step is to examine the nearby stellar environment to try to ascertain the probability that our solar system has been colonized. Finally, an observational /modeling approach is proposed to “search the skies” for signs of a local alien presence. Because this sky search can be incorporated into ongoing or proposed searches for asteroidal/cometary objects that might threaten the Earth, project-funding concerns might be eased.

And if we do detect a nearby alien presence, what then? Humanity would be faced with the dilemma of whether or not to signal, whether to bury its collective head in the sand or to strike out in anger and fear. A direct-contact protocol (6) would then be necessary as would widespread discussion of who speaks for Earth and where a meeting between humans and representatives of the alien species should occur.

(II) A Tale of Two civilizations

It can be argued that our assumptions about advanced galactic civilizations and their motives have more to do with human preconceptions than with ET’s activities. Since it is impossible to predict the course of our own civilization even a decade or two in advance, all of our preconceptions about the motives of advanced galactics must be taken with a large chunk of salt.

(A) The Communicatus

The standard SETI model for communicating extraterrestrial civilizations is based in part upon the model of Nikolai Kardashev (7), who was a leading Cold War era Soviet radio astronomer. Consider the hypothetical “Communicatus”, a race of technologically advanced extraterrestrials who evolve according to Kardashev’s model.

The Communicatus follow the basic human pattern of civilization up to the Cold War era. Evolved from carnivores, they experience in succession a long Stone Age which culminates in an agricultural revolution, then the metallurgical revolution of a Bronze and Iron Age. After discovering science, their technology rapidly develops in the direction of aircraft, spacecraft, radio, computers, and automobiles.

A long competition develops between two contending political powers upon their home world, one socialist and one capitalist. During that era, there are alternate periods of uneasy peace and limited hostilities. But instead of the capitulation of one or the other, the intense scientific competition between the two powers continues in an increasingly more ritualized fashion. Ultimately, the two social-political systems merge into a defacto world government.

In the golden age that follows the merger, the collective social responsibilities of the socialist competitor are aligned with the individual ingenuity of the capitalists. Poverty, hunger, and disease are all vanquished and the global society soon learns to productively tap all of the solar radiation reaching the home planet. All citizens of the fortunate world soon are leading long and productive lives and are contributing meaningfully to civilization’s advancement.

Expansion into the solar system begins, with the construction of freeflying space habitats from asteroidal and cometary material (8). Believing that their social structure is the most stable and successful for the needs of an expanding technological civilization on both the home world and off planet, the government of the home world elects to begin experimenting with radio signals beamed in the direction of suitable nearby sites of alien intelligence.

A binary code is developed so that any intelligent receiver will recognize the signals as artificial and readily interpret them. As the development of their home solar system continues, more energy for the transmissions becomes available through application of off-planet solar-power relay stations. The number of transmitting radio telescopes, the transmission range and the information-content of the message all increase with time.

In a sense, the Communicatus become a society of secular proselytizers. Perhaps by fortuitous accident, they have solved society’s ills and evolved as successfully on the material plane as possible. The reason for the continued funding of the interstellar transmissions is quasi-religious.

Most citizens believe that it is their responsibility to communicate the success of their social-political order to less fortunate galactic civilizations. Eventually, they hope, a galaxy-wide network of like-minded civilizations will develop. They anticipate that in the farther future, this network will be able to command galactic-scale resources and expand the interstellar transmissions to the intergalactic realm. Someday, all the universe will be fully awakened and communicative. Then consciousness will have fulfilled its purpose.

(B) The Mutatis

Up to a certain point, the cultural evolution of the “Mutatis” mirrors that of the Communicatus. They also evolve through cultural levels corresponding to the terrestrial Stone, Bronze, and Iron Ages. They also discover science, which leads to a rapid increase in the rate of technological advancement.

But their equivalent of the terrestrial Cold War ends in a manner analogous to the conclusion of that terrestrial conflict. The socialist-type Mutatis state capitulates to the capitalists.

Without any major international competition, the Mutatis capitalists construct a New World order that fails to satisfy some of the basic requirements of most world citizens. As Mutatis society develops, the gap between haves and have-nots increases. Educated citizens of the more advanced Mutatis nation states, a small but influential minority of the total world population, become increasingly disillusioned about the long-term possibilities for their civilization’s survival.

But salvation comes from an unexpected source. An Information Age had developed from the widespread application of computer technology initially developed for war. A world-wide network of personal computers had developed, an equivalent to our “World Wide Web.”

Originally developed as a means of sharing technical information during their Cold War, the Mutatis Web has now evolved into a tool for the more jaded and physically lazier Mutatis consumer. New forms of pornography, only available on the Web, can titillate all senses of the subscriber. Affluent web users can conduct all business and do their shopping from their console, without leaving the confines of their homes.

Driven by market pressures, the size and cost of the microprocessor chips that are the basis of the Web constantly decreases, information content of the chips consequently increases. In an experimental effort to emulate the complexity of the Mutatis brain on the Web, brain neurons are kept alive on computer chips. Eventually, these neurons are interfaced with the ever-complexifying network of the Web. The complexity of the evolving network soon greatly exceeds that of an individual Mutatis brain.

Neuronal interfaces are constructed so that the brains of Web subscribers can directly interact with the planet-wide network. Many citizens soon prefer the virtual reality of the Web to direct interaction with their fellows.

And then, entirely by accident, a user of the Web produces a social revolution of enormous importance. While hooked into the Web and participating in an especially graphic form of virtual pornography, an elderly and politically powerful citizen suffers the Mutatis equivalent of a fatal heart attack.

But, although his physical body has died, Web users over the planet soon notice the intruding presence of the powerful individual in their virtual worlds. The Holographic Theory of Consciousness (9) has been proven by the survival of the unfortunate individual’s mind.

Soon, the whole planet clamors for the cybernetic immortality attained by the deceased individual. Vast Web Emporia spring up all over the Mutatis home world, in which citizens can hook up to systems that preserve their bodies as long as possible while the minds of the occupants virtually surf the Web (10).

Social unrest disappears overnight as Web-connection replaces thoughts of revolution. Hunger disappears since the caloric cost of maintaining the slumbering bodies of the Web-users is much less than the cost of supporting a more physically active population. Fear of death also vanishes, since death just means the inability to return to one’s physical body after voyaging through the Web.

Soon, the individual conscious “subroutines” begin to link together. New conscious abilities emerge as complexity increases. The communal mind proposed by Olaf Stapledon (11) comes into existence not through telepathy and centralized planning, but through selfishness and greed.

Ultimately, Mutatis society grows very conservative with so many ancient minds permanently resident on the Web. The maintenance of the cybernetic network and the system of virtual immortality becomes the prime directive of all citizens of Mutatis both for those who are corporeal and those who are virtual.

The Mutatis Collective Mind begins to spread into space, not because of a desire to explore and not out of altruism towards distant galactics. The main motivation is continued immortality and the home solar system should be completely rebuilt to prevent dangerous impacts on the home world by asteroidal and cometary objects.

In the fullness of time, the Mutatis home star leaves the main sequence and begins to swell towards the subgiant and giant phases of its evolution. As the oceans of the home world evaporate, the collective mind, now housed among the assorted terminals of myriad Mutatis space habitats, begins to turn its attention to the nearer stars. In the interest of collective immortality, a long migration is planned.

(C) Which Type of ET Civilization are we Most Likely to Contact?

Although most scientists will be more sympathetic to the society and motivations of the Communicatus, the scenario of the Mutatis does not unduly strain credibility. It is impossible to predict who our closest galactic neighbors are ? talkative, altruistic explorers or quiet, inward-focussed immortals. (There are, of course, many additional possible scenarios for the evolution of a galactic civilization.)

We should continue “conventional” SETI radio searches in the hopes of hearing from Communicatus. But we should also investigate the possibility that Mutatis might exist, right here in the solar system. We next investigate the feasible forms of interstellar travel, to demonstrate that migration at the end of an advanced civilization’s home star’s main sequence life is not impossible.

(III) Feasible Interstellar Travel for Migrants

Starting from the pre-Space Age, many modes of interstellar travel have been suggested. Most can be rejected as unfeasible or impractical, at least for application to large-scale migrations. This essay introduces some of the most popular contending interstellar propulsion systems. Details of most of the proposed methods of interstellar travel have been reviewed in The Starflight Handbook and Prospects for Interstellar Travel (12, 13).

(A) Propulsion Systems that are not Presently Feasible

Probably the most popular method of interstellar travel among the general public is the “Hyperdrive”. Using magnetic fields or more esoteric means, the space/time warping characteristics of a collapsed star are simulated on a small scale and for long enough duration for a starship to take a dimensional shortcut to another star. A multi-light year voyage might take minutes. Unfortunately, although research in the construction of such artificial singularities is continuing (14), the field strengths required are so gargantuan that the hyperdrive will be found only among the pages of science fiction novels for the foreseeable future (15).

If a starship crew is capable of traveling at near-optic velocities, general relativistic time dilation greatly shortens the voyage’s duration, from the crew’s point of view. There are two conceptual methods of achieving such speeds that do not strain the laws of physics.

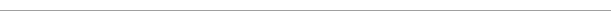

The Bussard Ramjet (Figure 1) works by using a magnetic scoop (or ramscoop) to ingest interstellar protons over a large area (16). The fuel passes through a fusion reactor capable of converting hydrogen directly into helium plus energy, as does the Sun and other main sequence stars. The released energy is used to accelerate the helium nuclei exhaust out the rear of the spacecraft. Although recent research indicates that a suitable ramscoop may be feasible (17), there seems to be no way to create a proton fusion reactor. Many less capable ramjet variants have been proposed, the most feasible is the use of a solenoidal field ramscoop to reflect oncoming interstellar ions and thereby decelerate a speeding starship (18, 19).

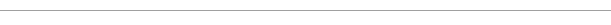

Technology and physics do not provide substantial barriers, on the other hand, for the Antimatter Rocket (20). Nuclear fission and fusion, those nuclear reactions currently in use by humans are relatively inefficient in that only a small percentage of the reactant mass is converted to energy. A fuel mix consisting of antiprotons (which can be produced in nuclear accelerators) and protons is the most volatile substance in the universe, on the other hand, since essentially all the reactant mass is converted into energy. Antiprotons can now be produced in small quantities and stored for long periods in “Penning Traps” (21). Although antimatter rocketry (Figure 2) is certainly feasible technologically, there is one “small” problem. The cost of antimatter production must fall by many orders of magnitude before the antimatter rocket can be considered economically feasible.

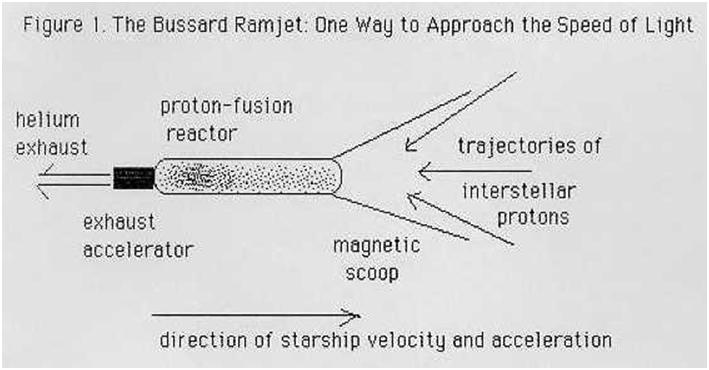

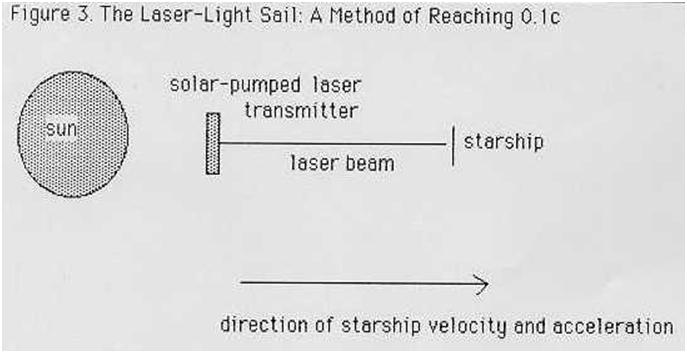

For decades or century duration interstellar voyages at speeds as high as 10% of the speed of light (0.1c), a favored propulsion system is the laser light sail (22). A solar-pumped laser power station is constructed in space and maneuvered into position between the Sun and the destination star. A laser beam from the power station impinges against the light sail of the starship – a highly reflective metal sheet with a thickness of nanometers or microns (Figure 3). The pressure of the laser photons accelerates the spacecraft in the direction of the destination target star. Optimum performance seems limited because of the requirement for the power station to be “suspended” between Sun and starship very accurately for decades, but projection instead of both power station and probe on the same initial slow hyperbolic trajectory towards the target star may somewhat alleviate pointing problems (23).

Since the recent experimental confirmation of the Casimir Effect (24), starship designers must consider the possibility that a future propulsion option might be energy from stabilized vacuum quantum fluctuations or controlled modification to a spacecraft’s inertia (25). Although a NASA workshop on these and related topics has occurred (26), it must be admitted that research in the field of ZPE (Zero Point Energy) is too underdeveloped at this time to comment on its ultimate utility for interstellar travel or other applications.

(B) Currently Feasible Propulsion Options

During the 1970’s and 1980’s, the first open literature engineering study of the difficulties of interstellar travel, Project Daedalus, was conducted by the British Interplanetary Society (27). At the conclusion of Daedalus, several of the team members collaborated on a consideration of what types of interstellar missions would be possible for humans, as opposed to robots, in the foreseeable future (28). After considering and eliminating the propulsion systems reviewed above, the Daedalus team members were left only two contenders. In contrast to science fiction, the only feasible mission was the “1000-year ark” or world ship (29, 30), in which the population of a kilometer-dimension ship with a closed ecosystem travels for many generations between neighboring stellar systems.

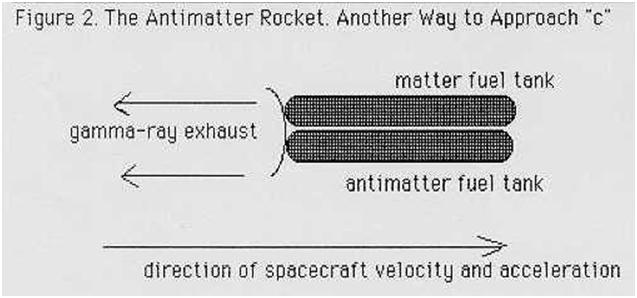

(1) Fusion Pulse

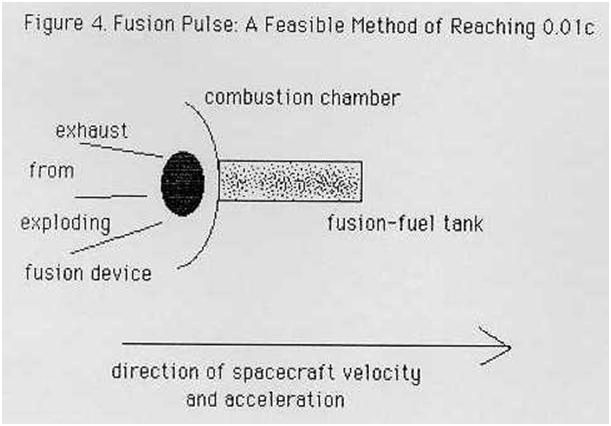

One method of world ship propulsion, a product of the Cold War, is nuclear pulse propulsion (Figure 4). Thrust is produced by the reaction of either a thermonuclear bomb external to the ship’s reaction product, or an electron beam (or laser beam) imploded inertial fusion micropellet (31, 32).

Possible reactants include deuterium/tritium, deuterium/helium-3, lithium-proton, and boron-proton. The deuterium/tritium thermonuclear fusion reaction is relatively easy to ignite, but has the disadvantage of producing copious amounts of thermal neutrons and a consequent radiation hazard. Although the deuterium/helium-3 reaction is much cleaner and almost as easy to initiate, helium-3 is extremely rare on the earth. We might obtain it though, directly from the solar wind, by mining upper lunar regolith layers that have been exposed for eons to the solar wind, or from the atmospheres of the giant planets. Although relatively clean and utilizing rather common reactants, the last two reactions listed are much more difficult to initiate.

The exhaust velocity of a fusion pulse starship might be in the range 0.01 – 0.03c (where c is the speed of light). If deceleration is accomplished using a magnetic field to decelerate reflect oncoming interstellar ions (18, 19), a fusion-propelled interstellar ark might require 500–1000 years to reach the nearest star. But until controlled fusion is actually achieved and the reactants are optimized, it is difficult to estimate whether an entire space-faring civilization could be relocated using fusion alone.

(2) The Hyper-thin Solar Sail

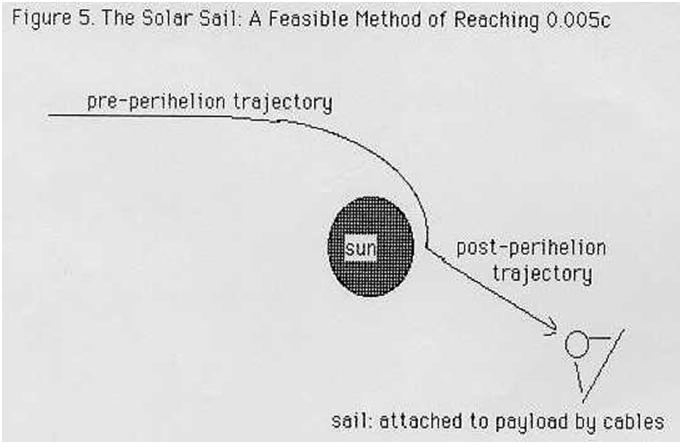

The only currently feasible alternative to fusion pulse propulsion is the hyper-thin solar sail unfurled near the sun (33, 34). A space manufactured, highly reflective sheet sail with a thickness measured in nanometers is attached to the payload with diamond strength (or silicon carbide) cable. After injection into a parabolic or slightly hyperbolic solar orbit, the sail is gradually unfurled as close to the Sun as possible. The sail/cables/payload is then “blown” out of the solar system by the radiation pressure of sunlight (Figure 5).

For a small interstellar ark massing a few million kilograms, the fully unfurled sail dimensions are typically about 100 km and peak accelerations are in the neighborhood of a few g (where 1 g = 1 Earth surface gravity). One-way voyage times to the nearest stars (Proxima and Alpha Centauri at an approximate distance of 4.3 light years) are typically about 1000 years.

After the acceleration phase, the cables and sail can be wound around the habitat to provide additional cosmic ray protection. As the target star approaches, the sail can be unfurled and used in reverse for deceleration.

A number of methods have been suggested to reduce travel time or increase payload. These include use of very thin and highly reflective cables that are partially supported by solar radiation pressure, a perforated sail surface to reduce sail mass, and more complex pre-perihelion trajectories (35 – 38). But the greatest trip-time reduction is caused by increasing the solar luminosity (34), which enhances this propulsion system’s utility for those civilizations relocating from a dying star.

(C) Solar Sail Operations from Post-Main-Sequence Stars

We assume here that an advanced galactic civilization might not commence interstellar migration until its home star leaves the main sequence. At that time, the star’s luminosity and physical size both increase.

To examine the effects of this stellar luminosity change upon solar sail performance, we next define a solar sail “runway”. This is the distance between sail partial unfurlment at perihelion and the point at which the sail is refurled. For the purposes of the argument presented here, assume that the sail is refurled when the distance to the Sun’s center has increased by a factor of 2X from the perihelion distance and the radiant flux received from the Sun (in watt/area) has decreased to one-quarter of its perihelion value. As the sail is unfurled along the runway, its radiation pressure acceleration radially outward from the Sun is here assumed to be constant.

For example, if the sail is partially unfurled at 0.02 AU (Astronomical Units) from the Sun’s center, the sail is refurled at 0.04 AU and the runway length is 0.02 AU. The perihelion distance is a function of the reflective and thermal properties of the sail and other aspects of sail design (33, 34).

Assuming the same sail design characteristics as above, imagine that the Sun is replaced by a star with twice the solar luminosity. Applying the inverse square law, the perihelion distance is now 0.028 AU from the star’s center for the same perihelion radiant flux on the sail. The sail is refurled at 0.056 AU and the runway length has increased to 0.028 AU. These arguments can be generalized to demonstrate that runway length, Srw, varies with the square root of stellar luminosity, Lstar.

Applying elementary kinematics, the sail’s velocity (relative to its star) at the conclusion of sail operation, vfin, can be written:

(1)

(1)

where a = starship acceleration on “runway” and v0 = starship perihelion velocity relative to its star.

Assuming that 2aSrw >> v0, the final starship velocity varies approximately with the square root of runway length or the fourth root of stellar luminosity.

This assumption can be checked for the case of a 1000X solar luminosity star, considered in Ref. 34. According to the approximate theory presented above, such a craft should be faster than an identical ship departing the Sun by a factor of the fourth-root of 1000, or about 5.6X.

Recent work (39, 40) has revealed that an optimum sail material is beryllium and that a 20 nm thick beryllium sail closely approximates the aluminum-boron bilayer sail performance presented in Fig. 3 of Ref. 34. From Ref. 40, a 20 nm thick sail can project a 1 x 107 kg payload to Alpha Centauri (at a distance of 4.3 light years), in about 1800 years, starting from a thermally limited perihelion distance of 0.02 1 AU and an initially parabolic solar orbit.

If the Sun were replaced by a giant star with 1000X the solar luminosity, the trip time to Alpha Centauri should be reduced by a factor of about 5.6X, to about 320 years. Note from Fig. 7 of Ref. 34 that the optimization program presented in that reference yields a corresponding travel time of about 300 years, which is in good agreement with the approximate theory presented here.

Even though the approximate dependence of starship final velocity with the fourth root of stellar luminosity is apparently confirmed by the above example, it should be treated as very approximate. Perihelion velocity may not always be negligible compared to the product of acceleration and runway length. The perihelion trajectory may not always be parabolic and the sail’s attitude at perihelion may not always be normal to the Sun, as assumed in Refs. 33, 34 and 40 (37, 38). For really accurate work, it will be necessary to treat the Sun or any other star as an extended light source if the perihelion distance is close, rather than as a point source as has been done in the optimization program in Ref. 34 (41).

The next section presents a sample sail-launched interstellar ark that could be flown from the Sun or a more luminous star. Stars in the solar vicinity are next examined to attempt to determine the frequency of post-main-sequence stars from which interstellar migration may be occurring. Starship velocities for expeditions leaving these systems will be estimated. From a consideration of stellar motions, an estimate is derived for the number of migrations to our solar system that may have occurred during the last billion years.

(IV) Nearby Stellar Candidates for Migrating Civilizations

Before examining various nearby candidate stars for the sites of migrating interstellar civilizations, some design considerations for a small interstellar ark are presented. These are based upon calculations using the solar sail optimization program presented in Ref. 34, for a 20 nm thick beryllium sail, for diamond tensile-strength cables, a rip-stop mesh array in front of the sail with an areal mass thickness of 1.24 x 10-5 kg/m2, and a sail unfurlment fraction of 0.25 at perihelion (40).

Table 1 presents characteristics of a small Sun-launched interstellar ark with a payload of 10 kg and a perihelion distance of 0.021 AU. This payload mass is similar to that of Gilfillan in an early treatment of interstellar arks (42) and suggested to Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin by this author for use in his science fiction novel with John Barnes, Encounter with Tiber (Warner, NY, 1996).

Table 1. Design Characteristics for a Small Sail-Launched Interstellar Ark

|

Payload: 105 kg |

Sail: 20 nm beryllium |

|

Cables: Diamond tensile strength |

Ripstop mesh thickness: 1.24 x 10-5 kg/m2 |

|

Perihelion: 0.021 AU |

Perihelion sail unfurlment fraction: 0.25 |

|

Unfurled sail radius: 120 km |

Total mass: 2.1 x 106 kg |

|

Peak acceleration: 6.33g |

Interstellar cruise velocity: 0.0036c |

|

Time to Alpha Centauri: 1193 years |

|

Such a large space-manufactured solar sail is a good way beyond the test sail unfurled at space station Mir in 1993 (43). It is also far beyond the Earth-launched sails under consideration today to propel an interstellar precursor probe early in the 21st century (44). Computer simulations of sail structural parameters do indicate that such a large sail craft could be engineered (45).

Some may argue that the example chosen is too small. But an interstellar colonizing expedition could consist of many ships of this type. The population of each might be around 20 (42). Also, if the goal is to create large space habitats or world ships from asteroidal and cometary material in the destination star system, not to reenter a gravity well and colonize a planetary system, the required mass budgets are of course more modest.

Attention is next turned to the stars in the solar neighborhood that might be home to a migrating interstellar civilization. Stars of interest are subgiant (luminosity class IV) and giant (luminosity class III) since civilizations around such stars have a strong motivation to emigrate.

(A) Procyon

Also called Alpha Canis Minor, the nearest candidate star (Procyon A) is classified as F5 IV-V, is in the process of leaving the main sequence and is located 11.3 light years from the Sun. It has a white dwarf companion (Procyon B) with 65% the Sun’s mass, at a mean separation of 4.55″, or 15 AU. The eccentricity of this binary star’s orbit is about 0.4 and the semimajor aids is 15.8 AU. The periastron of the orbit is about 7.63 AU, the apastron is approximately 17.35 AU. Procyon A has about 6X the solar luminosity and twice the Sun’s radius (46). From the mass-luminosity relationship, Procyon A has about 1.5X the mass of the Sun (47).

In their classic Planets for Man, Dole and Asimov estimate that a single F5 V star has a 0.0344 probability of possessing a habitable planet. This is only somewhat less than the 0.0545 probability of a Sunlike GOV star possessing a habitable planet (48).

But because F5 stars have a lower main sequence life expectancy than G and K main sequence stars and the proximity of its nearby white dwarf companion, analysts generally conclude that Procyon A is unlikely to possess life-bearing planets. Recently however, Whitmire et al. have reconsidered the likelihood of finding habitable planets in binary star systems (49).

Using Eq. (12) of Whitmire et al.’s analysis, the critical binary semi-major axis beyond which planet formation will not be inhibited at 1 AU from the primary star can be estimated as a function of secondary mass, orbital eccentricity, average planetesimal semimajor axis during planet formation and the critical planetesimal disruption velocity Uc (that value of planetesimal velocity required to disrupt the planet-formation process). Application of this equation reveals that Procyon A could possess a habitable planet if Uc is approximately 1000 m/sec. Whitmire et al. states that, in current planet-formation models, Uc >> 100 m/sec (49).

Therefore, Procyon A must be considered a marginal candidate for being the home star of a migrating interstellar civilization. If such a civilization is present there, the spacecraft considered in Table 1 departs from this 6X solar luminosity star at about 1.6X its velocity when launched from the Sun. At this velocity of 0.0056c, the craft could travel one light year in less than two centuries and reach the Sun in less than 2000 years.

(B) Beta Hydri

Dole and Asimov estimated that Beta Hydri, at 21.3 light years from the Sun, has a 0.037 probability of possessing a habitable planet (48). According to a recent study by Dravins et al. however, this single star should be classified as a G2 IV star (50).

The nearest subgiant, ? Hydri has an age of approximately 6.7 billion years and is slightly metal-poor. It is approximately 3.3X as luminous as the Sun (50).

The solar sail starship outlined in Table 1 would reach a velocity of about 0.0049c, if launched from ? Hydri. This ship could cover a distance of one light year in slightly more than 200 years, reach our solar system in about 4,400 years.

(C) Pollux

Pollux, also called Beta Geminorum, is 35 light years from the Sun and is classified as a KO III giant. Although not the nearest red giant, Pollux is the nearest giant star that may have spent its main sequence lifetime as an F-dwarf, which may have had habitable planets (51).

Currently, Pollux is about 35X as luminous as the Sun (51). If the starship considered in Table 1 departed Pollux, its interstellar cruise velocity would be about 0.0088c. This craft could traverse 1 light year in less than 115 years, but would require about 4,000 years to reach the Sun.

(D) The Effects of Stellar Motions

If an interstellar civilization is migrating from any of the three candidate stars considered above, it seems very unlikely that colony ships would reach our solar system. However, it must be emphasized that stars are not truly fixed in space; they all follow independent paths around the center of our Milky Way Galaxy.

Sometimes stars approach the Sun a lot closer than Proxima/Alpha Centauri at 4.3 light years. According to the results of a NASA JPL study of the Voyager space probes interstellar trajectories led by R. J. Cesarone, stars approach the Sun within distances of about 2 light years at intervals of approximately 100,000 years. Every million years or so, a star will approach the Sun within 1 light year (52).

Appendix 3 of The Starflight Handbook lists the nearest 74 star systems, out to about 21 light years (12). The list includes Procyon and ? Hydri, two candidate home stars for migrating interstellar civilizations. Conservatively, then one can reasonably expect that 1% of the stars in the solar neighborhood can be considered as candidate home stars for interstellar migrants.

During the past billion years, about 10,000 stars have approached the Sun within 2 light years, about 1,000 stars have approached the Sun within 1 light year. It is not unreasonable, therefore, to conclude that 10-100 candidate home stars for interstellar migrants have closely approached our solar system within the past billion years. It is therefore not impossible that space habitats constructed and occupied by interstellar migrants lurk in the depths of our solar system, waiting to be discovered.

(V) Conclusions: A New Approach to SETI

If starships have crossed to our solar system within past eons (perhaps accelerated by solar sails and decelerated by a combination of magnetic reflection of interstellar ions and solar sails), they may have created a myriad of artificial worldlets from asteroidal and cometary material. We may live within a “Dyson Sphere” (53) of millions of space habitats, each masquerading as a small comet nucleus or asteroid.

In the absence of directed radio transmissions from the extraterrestrials to the Earth, detection will be challenging, but not impossible. One method of detection might be a search for excess infrared emissions from asteroidal objects (5).

Consider the case of a 1 km radius spherical worldlet located 2 AU from the Sun. A system of mirrors is utilized to reflect sunlight into the worldlet’s interior, so that it’s internal temperature is 300 K (degrees Kelvin), a comfortable room temperature for humans. Such mirror systems have been proposed to supply solar energy for human space habitat designs (54).

To model reflected and emitted radiation from this object, the reflectivity (?) is assumed to be spectrally flat in the 0.3- 0.8 ? spectral range, where most of the Sun’s radiant flux is found. For the sake of this modeling exercise, it is assumed that ? = 0.1. If the habitat’s walls are fully opaque, the emissivity (?) is equal to 1-?, or 0.9 (55).

Located near Earth at 1 AU from the Sun, a flat plate oriented normal to the Sun receives about 1,400 watt/m2 of sunlight (47). At the 2 AU location of our hypothetical artificial worldlet, the solar radiant flux is reduced to about 350 watt/m2.

The total solar radiant power reflected (Sref) from the worldlet is equal to the product of its reflectivity, cross-sectional area, and the incident solar flux:

watts, (2)

watts, (2)

where rad = space habitat radius, in meters. For a 1000 meter spherical habitat at 2 AU from the Sun with a reflectivity of 0.1, about 108 watts of solar radiation are reflected into space.

Applying blackbody radiation theory (55), the radiant power of infrared reradiated by the spherical space habitat (Srad) can be written:

watts, (3)

watts, (3)

where T is the habitat’s absolute radiation temperature (here 300 K) and ? is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant (5.67 x 10-8 watt/m2K4). About 5 x 109 watts of infrared radiation will be radiated by this hypothetical space habitat, which is roughly 50X the radiant power of the reflected sunlight.

The size of the mirror necessary to reflect the required sunlight into the habitat can be estimated as follows. The amount of sunlight absorbed by the (fully opaque) habitat walls is 9X the amount reflected, or about 109 watts. To preserve the 300 K internal habitat temperature, about 4 x 109 watts of sunlight must be continuously supplied by the mirror. Since the solar radiant flux 2 AU from the Sun is about 350 watt/m2, the approximate mirror area required is about 107 square meters. If the mirror is disc shaped, its radius is about 2 km.

Mirror size of course depends upon worldlet location within the solar system. Smaller mirrors are required for habitats within the Near-Earth-Object (NEO) population, more distant Kuiper-Belt or inner-Oort-Belt worldlets require larger mirrors. It seems unlikely that we would confirm or detect an artificial worldlet’s existence by stray sunlight reflected in the Earth’s direction by the mirror since all or most of the light striking the mirror is directed into the habitat’s interior, probably through a system of windows (54).

Comparison of reflected solar spectral irradiance and reradiated infrared spectral irradiance (both in units of watts/m2–? ) has been accomplished using a published curve of the Sun’s spectral irradiance (56), corrected for the 2 AU habitat distance and a General Electric (GEN-15-C) Radiation Calculator (55). The peak spectral irradiance of the reflected flux is concentrated in near-visible waveband, mostly between 0.3 and 0.8 ?. Most of the infrared flux is concentrated in the 5 – 15 ? waveband.

Interestingly, the peak of both spectral irradiance curves is similar, in the neighborhood of 30 – 50 watts/m2–? . At 2.2 ? in the near infrared, the reflected solar spectral irradiance is about 1000X greater than the reradiated infrared spectral irradiance curve.

The situation would be different, however, if we moved our hypothetical alien space habitat from 2 AU to a position in the Kuiper Belt. If it were located at 50 AU, for example, the infrared flux would be the same, although a mirror radius of about 50 km would be required. But the reflected flux would be decreased by a factor of almost 1000X, so the two fluxes would be about equal at 2.2 microns. Interestingly, a recent photometric study of Kuiper Belt objects has revealed that some of them have emit more energy in the red/near-infrared spectral bands than expected (57). The reason for this color effect is unknown.

(A) A New SETI Search Strategy

Here, then, is the outline of a proposed research program to search for advanced extraterrestrials within the solar system:

- Small College and advanced amateur telescopes in the approximate aperture range 0.5 – 1 meters should be enlisted to search for NEOs that seem unnaturally smooth. Large terrestrial observatory instruments should applied in the same manner for Kuiper Belt objects. Such smooth objects would show less rotational brightness variation than objects of asteroidal or cometary origin. Such studies of NEOs and Kuiper Belt objects could be conducted in concurrence with present and future observational programs to inventory those objects that might pose a future collision threat to Earth.

- Modelers and theoreticians could devote themselves to accurate calculations of reflected and reradiated radiant fluxes and spectral irradiances for the many suggested shapes of space habitats – spheres, cylinders, toroids, etc. (54) – at a variety of distances from the Sun. This will allow determination of the optimum spectral wavebands to utilize in a search for artificial alien worldlets in the solar system.

- High altitude or space telescopes operating in the infrared wavebands selected should be used to check the selected smooth appearing objects for the predicted infrared excess radiation.

- A concomitant study among diplomats and international lawyers could determine an appropriate protocol for direct contact (6). If we locate nearby extraterrestrials, should we visit them, should they visit us, should a contact be by remote means only, or should we meet at a neutral location? We also need to determine (in the case of a direct face-to-face meeting) who should speak for humankind and how to respond if the aliens remain noncommunicative or display signs of hostility. Science fiction writers could contribute to this aspect of the study by developing multiple scenarios for the evolutionary paths of technologically advanced civilizations.

- A final step in the research project would be to determine whether tailored radar pulses (from Arecibo perhaps) could serve the dual purpose of mapping a suspicious body and initiating contact with the object’s suspected occupants.

We see that very conservative considerations of interstellar travel techniques demonstrate that extraterrestrials circling sub-giant or giant stars could relocate to neighboring stellar systems on trips requiring only a few centuries. As many as 100 such stars may have approached the Sun within 1 – 2 light years within the last billion years.

If technologically advanced extraterrestrial beings from these star systems have migrated to our solar system, they may have chosen to remain uncommunicative and may be living in space habitats within the Kuiper Belt or regions closer to the Earth. We should not be deterred by negative results to date in the search for Dyson Spheres circling nearby stars, since observational sensitivity limits such searches to heavily populated Dyson spheres that convert about 1% of the central star’s energy output to infrared “waste heat” (58).

It is up to the present generation of astronomers to begin the survey of small solar system objects to determine if any of them seem to be artificial. True, we may have to observe many thousands of asteroids or comets to find a likely candidate. But “conventional” SETI searchers are used to laborious searches since they must investigate hundreds or thousands of stars in the hope of finding one communicative civilization. Perhaps a broadened search strategy will enlarge the likelihood of a successful detection.

The research project proposed could utilize the talents of graduate students and scholars in a wide range of disciplines. The cost need not be outrageous and the results may change humanity’s conception of the universe and the role of technologically advanced conscious life.

References and Notes

- C. B. Cosmovici, S. Boyer, and D. Werthimer (eds.), Astronomical and Biochemical Origins and the Search for Life in the Universe, Editrice Compositori, Bologna, Italy, 1997, pp. 585-7 18.

- J. F. Kasting, D. P. Whitmire, and R. T. Reynolds,’Habitable Zones Around Main Sequence Stars’, Icarus, 74, 108-128 (1993).

- A. Hansson, Mars and the Development of Life, 2nd. ed., Wiley, NY, 1997.

- T. B. McCord, G. B. Hanssen, F. P. Fanale, R. W. Carlson, D. L. Matson, T. V. Johnson, W. D. Smythe, J. K. Crowley, P. D. Martin, A. Occampa, C. A. Hibbitts, J. C. Granahan, and the NIMS Team, ‘Salts on Europa’s Surface Detected by Galileo’s Near Infrared Mapping Spectrometer’, Science, 280, 1242-1245 (1998).

- M. D. Papagiannis, ‘An Infrared Search in Our Solar System as Part of a More Flexible Search Strategy’, in The Search for Extraterrestrial Life: Recent Developments, ed. M. D. Papagiannis, D. Reidel, Boston, MA, 1985, pp. 505-511.

- P. Schenkel, ‘Legal framework for Two Contact Scenarios’, J. British Interplanetary Soc. (JBIS), 50, 258-262 (1997).

- S. J. Dicke, The Biological Universe, Cambridge U. P., NY, 1996, pp. 435-436.

- G. K. O’Neill, The High Frontier, Morrow, NY, 1977.

- D. Bohm, Wholeness and the Implicit Order, Routledge & Kegan Paul, Boston, MA, 1980.

- F. J. Tipler, The Physics of Immortality, Doubleday, NY, 1994.

- 0. Stapledon, Last & First Men and Starmaker, Dover, NY, 1968. (This is a re-publication: Starmaker was first published in 1937.)

- E. Mallove and G. Matloff, The Starflight Handbook, Wiley, NY, 1989.

- J. H. Mauldin, Prospects for Interstellar Travel, Univelt, San Diego, CA, 1992.

- C. Maccone, ‘A Classification of Quadric Wormholes According to the “Matter” Requested for Interstellar Travel’, JBIS, 51, 184-194 (1998). Also see cited papers by G. A. Landis and E. W. Davis.

- G. L. Matloff, ‘Wormholes and Hyperdrives’, Mercury, 25, no. 4, 10-14 (July/August 1996).

- R. W. Bussard, ‘Galactic Matter and Interstellar Flight’, Astronautica Acta, 6, 179-194 (1960).

- B. Cassenti, ‘Design Concepts for the Interstellar Ramjet’, JBIS, 46, 151-160 (1993).

- G. L. Matloff and A. J. Fennelly, ‘A Superconducting Ion Scoop and its Application to Interstellar Flight’, JBIS, 27, 663-673 (1974).

- D. Andrews and R. Zubrin, ‘Magnetic Sails and Interstellar Travel’, JBIS, 43, 265-272 (1990).

- R. L. Forward and J. Davis, Mirror Matter: Pioneering Antimatter Physics, Wiley, NY, 1988.

- G. Gaidos, R. A. Lewis, K. Meyer, T. Schmidt, and G. A. Smith, ‘AIMstar: Antimatter Initiated Microfusion for Precursor Interstellar Missions’, in Missions to the Outer Solar System and Beyond: 2nd IAA Symposium on Realistic Near-Term Advanced Scientific Space Missions, ed. G. Genta, Levrotto & Bella, Torino, Italy, 1998, pp. 111-114.

- R. L. Forward, ‘Roundtrip Interstellar Travel Using Laser-Pushed Lightsails, J. Spacecraft & Rockets, 21, 187- 195 (1984).

- G. Matloff and S. Potter, Near Term Possibilities for the Laser Light Sail, in Missions to the Outer Solar System and Beyond: 1st IAA Symposium on Realistic Near-Term Advanced Scientific Space Missions, ed. G. Genta, Levrotto & Bella, Torino, Italy, 1996, pp. 53-64.

- S. K. Lamoreaux, ‘Demonstration of the Casimir Force in the 0.6 to 6 ? Range’, Physical Review Letters, 78, 5-8 (1997).

- H. E. Puthoff, ‘The Energetic Vacuum: Implications for Energy Research’, Speculations in Science and Technology, 13, 247-248 (1990).

- NASA/Lewis Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Workshop, Cleveland, OH, Aug. 12-14, 1997. Proceedings to be published, edited by M. Millis.

- A. R. Martin, ed., Project Daedalus: the Final Report on the BIS Starship Study, supplement to JBIS (1978).

- A. R. Martin, ‘World Ships: Concept, Cause, Cost, Construction, and Colonization’, JBIS, 37, 243-253 (1984).

- L. R. Shepherd, ‘Interstellar Flight’, in Realities of Spacetravel, ed. L. J. Carter, McGraw-Hill, NY, 1957, pp. 395-416.

- M. G. de San, ‘The Ultimate Destiny of an Intelligent Species-Everlasting Nomadic Life in the Galaxy’, JBIS, 34, 219-238 (1981).

- F. J. Dyson, ‘Interstellar Transport’, Physics Today, 21, no. 10, 41-45 (Oct. 1986).

- A. Bond and A. R. Martin, ‘The Propulsion System, Parts 1 and 2’, in Project Daedalus: the Final Report on the BIS Starship Study, ed. A. R. Martin, supplement to JBIS (1978), pp. 44-82.

- G. L. Matloff and E. F. Mallove, ‘Solar Sail Starships: Clipper Ships of the Galaxy’, JBIS, 34, 371-380 (1981).

- G. L. Matloff and E. F. Mallove, ‘The Interstellar Solar Sail: Optimization and Further Analysis’, JBIS, 36, 201-209 (1983).

- G. L. Matloff, ‘The Impact of Nanotechnology upon Interstellar Solar Sailing and SETI’, JBIS, 49, 307-312 (1996). Also see G. L. Matloff and B. N. Cassenti, ‘Interstellar Solar Sailing: the Effect of Cable Radiation Pressure’, IAA.4.1-93-709.

- G. L. Matloff, ‘An Approximate Heterochromatic Perforated Light-Sail Theory’, IAA-95-IAA.4.1.01.

- G. Vulpettti, ‘Sailcrafts at High Speed by Orbital Angular Momentum Reversal’, Acta Astronautica, 40, 733-758 (1997). Also see G. Vulpetti, ‘3D High Speed Escape Heliocentric Trajectories for All-Metallic -Sail Low-Mass Sailcraft’, Acta Astronautica, 39, 161-170 (1996).

- B. Cassenti, ‘Optimization of Interstellar Solar Sail Velocities’, JBIS, 50, 475-478 (1997).

- G. A. Landis, ‘Small Laser-Propelled Interstellar Probe’, JBIS, 50, 149-154 (1997).

- G. L. Matloff, ‘Interstellar Solar Sails: Projected Performance of Partially Transmissive Sail Films’, IAA-97-IAA.4.1.04.

- C. P. McInnes and J. F. L. Simmons, ‘Solar Sail Halo Orbits I’, J. Spacecraft & Rockets, 29, 466-471 (1992).

- E. S. Gilfillan, Jr., Migration to the Stars: Never Again Enough People, Luce, NY, 1975.

- G. Pignolet, 0. Boisard, E. Dutet, and A. Perret, ‘Sailing Europe into the Future of Space’, in Missions to the Outer Solar System and Beyond: 1st IAA Symposium on Realistic Near-Term Advanced Scientific Space Missions, ed. G. Genta, Levrotto & Bella, Torino, Italy, 1996, pp. 49-51.

- G. Genta and E. Brusca, ‘The Aurora Project: A New Sail Layout’, in Missions to the Outer Solar System and Beyond: 2nd IAA Symposium on Realistic Near-Term Advanced Scientific Space Missions, ed. G. Genta, Levrotto & Bella, Torino, Italy, 1998, pp. 69-74.

- B. N. Cassenti, G. L. Matloff, and J. Strobl, ‘The Structural Response and Stability of Interstellar Solar Sails’, JBIS, 49, 345-350 (1996).

- R. Burnham, Jr., Burnham’s Celestial Handbook, Dover, NY, 1978.

- E. Chaisson and S. McMillan, Astronomy Today, 2nd ed., Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 1996.

- S. H. Dole and I. Asimov, Planets for Man, Random House, NY, 1964.

- D. P. Whitmire, J. J. Matese, L. Criswell, and S. Mikkola, ‘Habitable Planet Formation in Binary Star Systems’, Icarus, 132, 196-203 (1998).

- D. Dravins, L. Lindegren, and D. A. VandenBerg, ‘Beta Hydri (G2 IV): A Revised Age for the Closest Subgiant’, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 330, 1077-1079 (1996).

- G. L. Matloff and J. Pazmino, ‘Detecting Interstellar Migrations’, in Astronomical and Biochemical Origins and the Search for Life in the Universe, eds. C. B. Cosmovici, S. Boyer, and D. Werthimer, Editrice Compositori, Bologna, Italy, 1997, pp. 757-759.

- R. J. Cesarone, A. B. Sergeyevsky, and S. J. Kerridge, ‘Prospects for the Voyager Extraplanetary and Interstellar Mission’, JBIS, 37, 99-116 (1984).

- F. J. Dyson, ‘Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infrared Radiation’, Science, 131, 1667 (1959).

- R. D. Johnson, ed., NASA SP-413: Space Settlements – A Design Study, NASA, Washington, DC, 1977.

- W. L. Wolfe, Handbook of Military Infrared Technology, Office of Naval Research, Dept. of the Navy, Washington, DC, 1965.

- J. C. Lindsay, W. M. Neupert, and R. G. Stone, ‘The Sun’, in Introduction to Space Science, ed. W. N. Hess, Gordon and Breach, NY, 1965, pp. 585-630.

- S. C. Tegler and W. Romanishin, ‘Two Distinct Populations of Kuiper Belt Objects’, Nature, 392, 49-51 (1998). Also see ‘The Kuiper Belt’s Dual Colors’, Sky & Telescope, 96, no. 2, 24 (August 1998).

- J. Jugaku and S. Nishimura, ‘A Search for Dyson Spheres Around Late-Type Stars in the Solar Neighborhood II’, in Astronomical and Biochemical Origins and the Search for Life in the Universe, eds. C. B. Cosmovici, S. Boyer, and D. Werthimer, Editrice Compositori, Bologna, Italy, 1997, pp. 707-709.

4 Replies to “Re-Enchantment of the Solar System”

Comments are closed.